The Oracle Within: Operationalizing Collective Intelligence for Strategic Advantage in the Enterprise

Learn how enterprise prediction markets outperform expert forecasts, reduce project failures, and drive smarter capital allocation decisions.

Executive Summary

The modern enterprise faces an epistemological paradox: while it possesses more data than at any point in history, its capacity for accurate foresight remains critically impaired by archaic decision-making structures. Despite billions invested in data lakes, business intelligence platforms, and advanced analytics, the "last mile" of strategic forecasting—the synthesis of dispersed information into a coherent probability—is frequently relegated to hierarchical consensus. This phenomenon, often driven by the "Highest Paid Person’s Opinion" (HiPPO) effect, results in a systemic suppression of ground-level truth, leading to catastrophic project failures, missed market transitions, and capital misallocation.

Global estimates indicate that enterprises write off approximately $500 billion annually in failed software projects alone, a figure that serves as a grim proxy for the broader costs of strategic misalignment.1 These failures rarely stem from a total absence of information; rather, they arise from the inability to aggregate the fragmented, private knowledge held by distributed employees and transform it into actionable intelligence.

This report advocates for a paradigm shift in corporate governance: the deployment of internal Prediction Markets. By adapting the mechanisms of financial markets to the information economy of the firm, enterprises can bypass the social and cognitive biases that plague committee-based forecasting. Evidence from deployments at Hewlett-Packard, Google, and Ford demonstrates that prediction markets consistently outperform expert forecasts and traditional consensus mechanisms, achieving accuracy improvements of 25% or more.2 Furthermore, an analysis of the 2024 U.S. election prediction markets reveals critical lessons on liquidity, incentive design, and the distinction between "smart money" and "noise," providing a blueprint for corporate implementation.

The prediction market is not merely a forecasting tool; it is a mechanism for collective truth-seeking. It creates a meritocracy of ideas where accuracy is rewarded, bias is penalized, and the "optimism" that obscures risk is stripped away by the cold calculus of price discovery. This document outlines the business case, theoretical underpinnings, empirical evidence, and operational roadmap for establishing a prediction market capability as a core strategic asset.

1. The Epistemological Crisis of the Modern Enterprise

1.1 The High Cost of the "Known Unknowns"

The contemporary corporate landscape is littered with the wreckage of initiatives that failed not because the risks were unknowable, but because they were unknown to leadership. In the typical hierarchical organization, information travels upward through a series of filters. At each layer of management, nuance is stripped away, probabilities are hardened into certainties to signal confidence, and inconvenient data points are excised to align with political expediencies. By the time intelligence reaches the C-suite, it has been sanitized into a "Green" status report, even when the engineers on the ground know the project is definitively "Red."

This disconnect manifests in the staggering rate of corporate project failure. Research highlights that 31% of software projects are cancelled before completion, and 53% exceed their budgets by nearly 190%.1 These are not merely operational inefficiencies; they represent a fundamental failure of information aggregation. The "truth" about these projects—that the technology was immature, the deadline unrealistic, or the vendor unreliable—was almost certainly known by individuals within the organization months before the official cancellation. However, without a mechanism to capture and aggregate this dispersed knowledge, the enterprise remained blind.

1.2 The Pathology of Consensus: HiPPOs and Groupthink

The primary obstacle to accurate forecasting in the enterprise is the social dynamic of decision-making. Strategic forecasts are typically generated in meetings, environments that are uniquely hostile to truth-telling. The "HiPPO" effect—deference to the Highest Paid Person's Opinion—creates a distortion field where the leader's initial hypothesis acts as an anchor.5 Lower-status employees, who often possess the most relevant "ground truth," are disincentivized from contradicting senior leadership. To do so is to risk social capital and career progression.

Consequently, groups drift toward Groupthink, a psychological phenomenon where the desire for harmony and conformity overrides the realistic appraisal of alternatives.6 This results in "Optimism Bias," a systematic tendency to overestimate the likelihood of positive outcomes and underestimate the time and resources required for success.7 In a committee, optimism is often conflated with loyalty. The skeptic is labeled "not a team player," while the optimist is rewarded for their "can-do attitude," even if their forecast is objectively delusional.

1.3 The Limitations of Expert Forecasting

Enterprises often seek to mitigate internal bias by hiring external experts. However, research by Philip Tetlock and others has demonstrated that experts are frequently no more accurate than chance in predicting complex, geopolitical, or economic outcomes.8 Experts suffer from "domain myopia"—they focus intensely on their specific area of knowledge (the "inside view") while ignoring broader statistical base rates (the "outside view"). Furthermore, experts are often incentivized to produce narratives that sound authoritative rather than probabilistic forecasts that acknowledge uncertainty. A prediction market, by contrast, aggregates the inputs of both the expert and the generalist, weighting them not by their credentials but by their demonstrated track record and conviction.

2. The Prediction Market Solution: Mechanisms and Theory

To address these structural failures, we must look to the theoretical foundations of information aggregation. The prediction market is an application of the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) to the internal economy of the firm.

2.1 Hayek and the Price Mechanism

The intellectual lineage of the prediction market traces back to Friedrich Hayek’s seminal 1945 work, The Use of Knowledge in Society. Hayek argued that in any complex system, knowledge is never given in its totality to a single mind. Instead, it exists as dispersed "bits of incomplete and frequently contradictory knowledge" held by separate individuals.9 The central planner (or CEO) cannot possibly aggregate this information efficiently through bureaucratic channels.

Hayek identified the price mechanism as the solution. In a functioning market, a price is a signal wrapped in an incentive. It communicates information about scarcity, demand, and utility without requiring participants to understand the underlying causes. When the price of a prediction market contract for "Project X will launch on time" drops from $0.80 to $0.40, it sends a clear, unadulterated signal: confidence has collapsed. This price change aggregates the private knowledge of the QA tester who found a bug, the supply chain manager seeing a delay, and the finance analyst noting a budget variance—all without a single meeting or status report.11

2.2 Surowiecki’s Criteria for Collective Wisdom

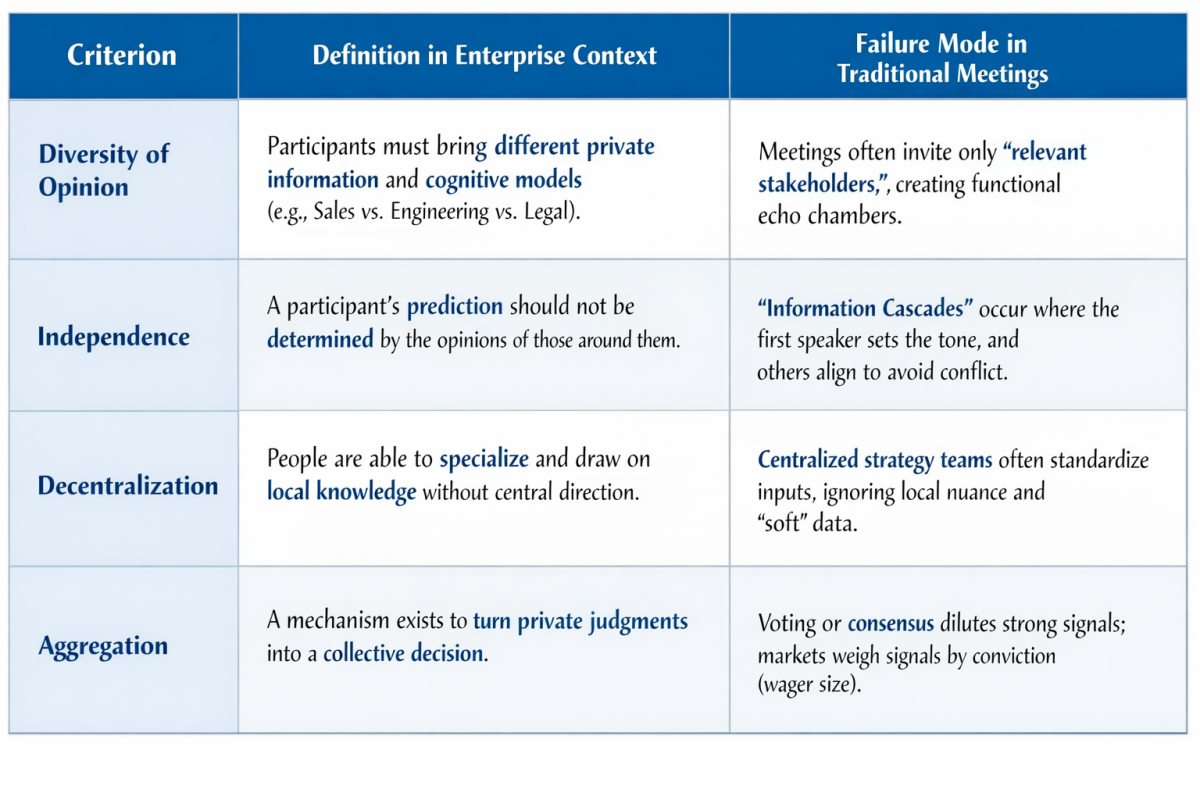

In The Wisdom of Crowds, James Surowiecki outlines the specific conditions under which a group’s collective judgment is superior to that of the smartest individual within it. These conditions serve as the design specifications for a successful enterprise prediction market:

Prediction markets operationalize these criteria. Anonymity ensures independence; the open market platform ensures diversity; and the automated market maker handles aggregation.

2.3 The Mechanism of Truth: How It Works

In a standard binary prediction market, participants trade contracts that pay out $1.00 if an event occurs and $0.00 if it does not. The current trading price represents the market's consensus probability. If a contract trades at $0.60, the market assigns a 60% probability to the event occurring.

This mechanism transforms forecasting from a political act into an investment act. In a meeting, talk is cheap. In a market, "money talks." If an employee believes a project will fail, but the internal status is "Green," they can buy "No" shares at a discount. This potential for profit (whether in real money, virtual currency, or reputation points) creates a powerful incentive to reveal private information and correct the public record.

3. Empirical Evidence: The Corporate Track Record

The theoretical promise of prediction markets has been validated by empirical deployments in some of the world’s most data-driven enterprises. These case studies demonstrate that markets are not just theoretical constructs but practical tools for extracting "alpha" from internal data.

3.1 Hewlett-Packard (HP): The Seminal Experiment

One of the earliest and most rigorous experiments was conducted at Hewlett-Packard Labs to forecast printer sales. HP established a market where a small group of mid-level managers (20–60 participants) bought and sold shares predicting monthly sales figures.

-

The Results: The prediction market forecasts were more accurate than the official corporate forecasts in 75% of the events (12 out of 16 months).4

-

The Mechanism: The official forecast was a product of a bureaucratic process involving targets and quotas, which introduced bias. Sales managers had an incentive to "sandbag" (under-promise) to ensure they hit their bonuses, while executives had an incentive to inflate targets to please shareholders. The prediction market, however, allowed these same individuals to bet anonymously on what they actually thought would happen. The market aggregated their honest assessments, stripping away the strategic posturing inherent in the quota setting process.

3.2 Google: "Googles" and the Optimism Bias

Google ran an extensive internal prediction market for over two years, involving thousands of employees and a virtual currency called "Googles" (convertible to prizes). The markets covered topics ranging from product launch dates to the number of Gmail users.

-

Accuracy: The markets were remarkably efficient, predicting launch dates with greater precision than internal project timelines.2

-

The Optimism Bias Discovery: Researchers Cowgill and Zitzewitz analyzed the trading data and found a persistent "optimism bias" in the early trades—employees were naturally bullish on their own company, leading to inflated probabilities for positive outcomes. However, the study revealed a critical self-correcting mechanism: experienced traders learned to identify this bias and trade against it. This "arbitrage" behavior—betting against the company's hopes—removed the bias from the price over time. This finding confirms that markets are learning systems; they do not just aggregate information; they train participants to become less biased.2

-

Information Topology: The study also revealed that information flowed through informal social networks. Traders who sat near each other or shared hobbies tended to trade similarly, allowing the company to map its actual information flow, which differed significantly from the org chart.14

3.3 Ford Motor Company: Features and Sales

Ford implemented prediction markets to forecast weekly vehicle sales and the popularity of specific features on new models.

-

Beating the Experts: The market forecasts outperformed the professional experts employed by Ford to predict sales, achieving a 25% reduction in Mean Squared Error (MSE).2

-

Peripheral Wisdom: Ford's experiment highlighted the value of "peripheral wisdom." While the expert forecasters were isolated in headquarters, the market included participants from the dealer network, marketing, and finance. These individuals possessed diverse, local knowledge—e.g., feedback from a customer on a test drive—that the experts' models could not capture. The market successfully aggregated this unstructured data into a superior quantitative forecast.

3.4 Intel and "Firm X": Managing Capacity and Confidence

Intel used prediction markets to manage capacity planning—a high-stakes game where underestimating demand loses sales and overestimating leaves billion-dollar factories idle. Similarly, an anonymous conglomerate ("Firm X") used markets to predict project completion dates.

-

Combating Overconfidence: The market creator at Firm X explicitly stated the goal was to combat overconfidence: "People either say 'X will happen' or 'X won't happen.' They fail to think probabilistically." The market forced managers to attach a specific probability (e.g., 60%) to their confidence, leading to better calibration.2

-

The Marginal Trader: These experiments also demonstrated that markets can function effectively even with low liquidity ("thin markets"). The "Marginal Trader Hypothesis" posits that a market does not need thousands of participants to be accurate; it only needs a few informed traders with sufficient conviction (capital) to drive the price to the correct value.2

4. Public Markets as a Laboratory: Lessons from the 2024 Election

The 2024 U.S. election cycle served as a massive, real-world laboratory for comparing different prediction market designs. Analyzing the performance of public platforms offers crucial lessons for enterprise implementation, particularly regarding the relationship between volume, regulation, and accuracy.

4.1 The "Volume Trap": Why More Money Didn't Mean More Truth

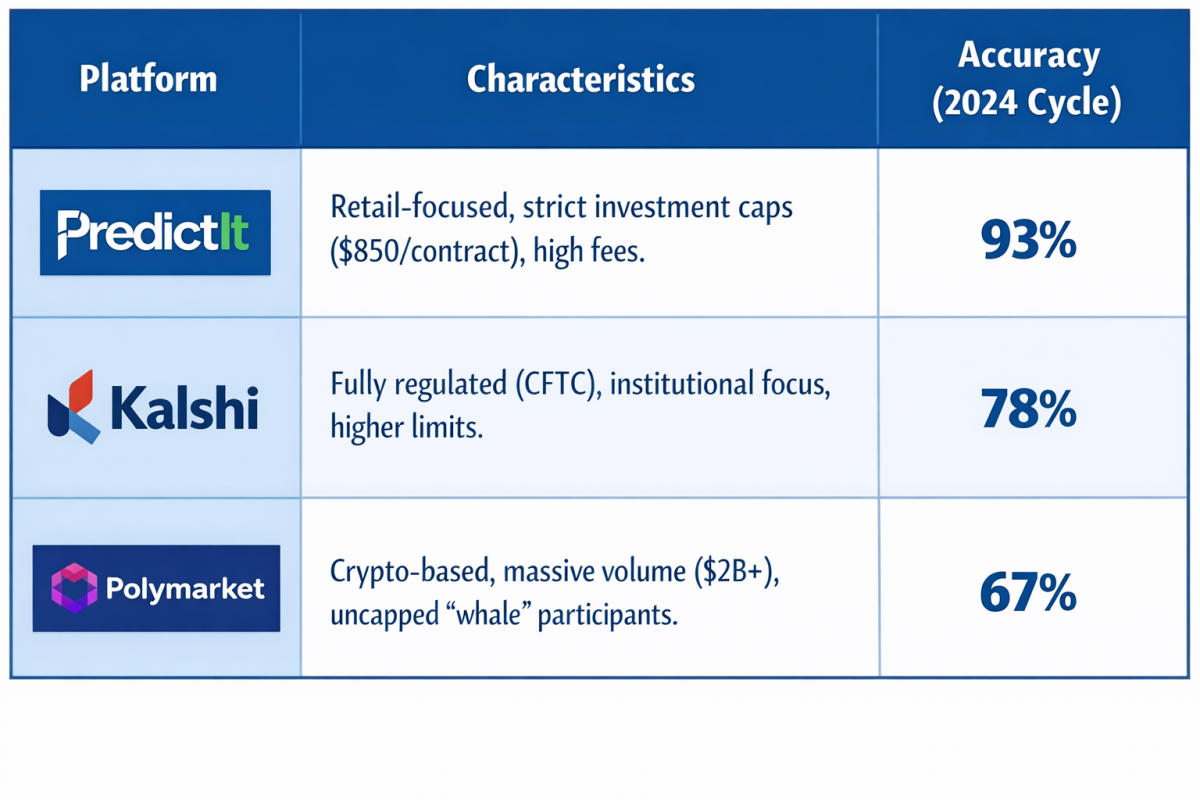

A landmark study by Vanderbilt University analyzed 2,500 markets across three major platforms: PredictIt (academic/retail, capped limits), Kalshi (regulated, institutional), and Polymarket (crypto/offshore, high volume).16 The results challenged the conventional wisdom that "Liquidity is King."

Insight for the Enterprise: The platform with the least volume (PredictIt) had the highest accuracy. This phenomenon, termed the "Volume Trap," suggests that high-volume markets can be distorted by "noise traders"—participants betting based on ideology, momentum, or herd behavior rather than information. PredictIt’s low limits prevented any single wealthy individual from dominating the market, forcing the price to reflect a broad consensus of diverse, smaller traders—a purer form of the "Wisdom of Crowds".17

Recommendation: Enterprises should consider position limits (caps on how much one employee can bet). This prevents a "corporate whale" (e.g., a senior executive with deep pockets or high status points) from buying the outcome they want to happen, thereby drowning out the signal from junior employees who know what will happen. Accuracy correlates with the diversity of informed traders, not just the raw volume of currency.

4.2 The "French Whale" and the Incentive for Deep Diligence

While Polymarket had lower overall accuracy across all contracts, it correctly called the presidential winner when polls were a toss-up, largely due to a single trader known as "Théo" (the "French Whale"). Théo bet over $30 million on Donald Trump, a position that many dismissed as manipulation or bias.

-

The Reality: Théo was not gambling blindly. He had commissioned his own private "neighbor polls"—a technique that asks "Who will your neighbor vote for?" to bypass the social desirability bias where voters lie about supporting controversial candidates.20 His data revealed a hidden strength for Trump that traditional experts missed.

-

The Incentive Mechanism: The massive financial upside of the prediction market ($80 million profit) incentivized Théo to fund a superior, labor-intensive data collection methodology.

-

Enterprise Application: This validates the concept of "Deep Diligence." In an enterprise, a prediction market incentivizes employees to perform the corporate equivalent of "neighbor polling." They will dig into obscure technical appendices, cross-reference supplier logs, and analyze raw customer support tickets—sifting through the corporate "garbage" to find the signal that gives them a trading edge.22 The market monetizes the act of paying attention to detail.

5. Incentives: Supercharging Data Collection

The engine of a prediction market is its incentive structure. Unlike a survey, which relies on altruism or compliance, a market relies on self-interest. This fundamental shift supercharges data collection in two ways: revealing private information and encouraging research.

5.1 Eliciting Private and Unverifiable Information

Standard knowledge management systems are passive; they wait for users to upload documents. Prediction markets are active; they pull information out of people. This is particularly valuable for "soft" information that is difficult to verify objectively.

Research into Bayesian Truth Serum (BTS) mechanisms shows that markets can be designed to elicit honesty even about subjective states (e.g., "Is team morale high?"). By asking participants not just for their own answer, but for their prediction of how others will answer, the mechanism creates a scoring rule where truth-telling maximizes the expected reward.25 In a corporate setting, this allows leadership to take the "emotional temperature" of the organization with a precision that anonymous surveys—plagued by low response rates and apathy—cannot match.

5.2 Sifting Through the Garbage: The Value of Alternative Data

In financial markets, traders use "alternative data"—satellite imagery of parking lots, credit card transaction logs, and social media sentiment—to gain an edge.27 The corporate prediction market introduces this dynamic internally.

Consider a market predicting "Will Competitor Y launch a rival product by Q3?" An employee in procurement might notice that the competitor has suddenly booked capacity at a shared supplier. An employee in HR might notice the competitor is aggressively hiring specific engineering talent. Individually, these are weak signals ("garbage" data). But the employee who spots them can trade on them, and the market aggregates these weak signals into a strong probability. The profit motive encourages employees to become information scavengers, turning the entire workforce into a distributed intelligence agency.

6. Being Better Than Experts: The Psychology of Prediction

Why do markets consistently beat experts? The answer lies in the distinction between knowledge creation and knowledge aggregation, and the psychological traits of successful forecasters.

6.1 The Expert's Blind Spot vs. The Superforecaster

Experts are essential for creating complex systems, but they are often poor forecasters. They suffer from overconfidence and rigid mental models. In contrast, prediction markets naturally identify and empower Superforecasters—individuals who possess a specific cognitive style characterized by:

-

Probabilistic Thinking: They think in percentages, not certainties.

-

Active Open-Mindedness: They constantly update their beliefs in response to new information.

-

Granularity: They distinguish between a 60% chance and a 65% chance.8

The BIN Model (Bias, Information, Noise) explains that accuracy comes from reducing bias and noise while maximizing information. Markets achieve this automatically. A noisy or biased trader loses money and influence over time, while a superforecaster accumulates capital and influence. The market is an automated filter that suppresses the "HiPPO" and amplifies the superforecaster.31

6.2 Truth-Telling as a Hedge Against Optimism

In a hierarchical organization, truth is political. Telling the CEO that their pet project is doomed is a career-limiting move. In a prediction market, "shorting" the CEO's project is a profit-generating move. This creates a Truth-Telling Mechanism that operates outside the chain of command.

-

Case in Point: If a project status is reported as "Green" (On Track) in the boardroom, but the prediction market contract is trading at $0.20 (20% chance of on-time delivery), the divergence acts as a fire alarm. It forces leadership to ask, "What does the crowd know that the project manager isn't telling us?" This early warning system allows for course correction before capital is irretrievably sunk.

7. Not 100% Accurate, But the "Least Wrong" Mechanism

A common critique of prediction markets is that they are not perfectly accurate. They missed Brexit; they missed the 2016 Trump victory (though they gave him higher odds than polls). However, this critique misunderstands the nature of probabilistic forecasting.

7.1 Probabilistic, Not Prophetic

A market prediction of 20% means the event should happen 2 times out of 10. If the event occurs, the market was not "wrong"; the improbable outcome materialized. The goal of the enterprise is not prophecy, but calibration—having a realistic assessment of risk. A calibrated forecast of 20% allows for better hedging and resource allocation than a false certainty of 0% or 100%.

7.2 The Paradox of Self-Defeating Prophecies

In a corporate setting, a "failed" prediction can actually be a massive strategic success. This is the phenomenon of the Self-Defeating Prophecy.

-

Scenario: A market predicts a key product launch has only a 10% chance of meeting its deadline.

-

Action: Alerted by this signal, management intervenes, allocates additional budget, and brings in a "tiger team" to fix the bottlenecks.

-

Outcome: The product launches on time.

-

Analysis: Technically, the market was "wrong" (it predicted delay). But functionally, the market saved the project. The value of the market lies in its ability to spur intervention. It is a decision-support tool, not a crystal ball.

8. Operationalizing the Market: Design and Governance

To operationalize this capability, the enterprise must move beyond the "suggestion box" and build a robust market infrastructure.

8.1 Market Design: Automated Market Makers (LMSR)

Early prediction markets used Continuous Double Auctions (CDA), similar to the stock market, where buyers match with sellers. In corporate settings, participant numbers are often too low to support this, leading to liquidity crunches.

-

The Solution: Modern enterprise platforms use an Automated Market Maker (AMM), typically based on the Logarithmic Market Scoring Rule (LMSR).2 The AMM acts as the "house," always willing to buy or sell at a price determined by an algorithm. This ensures that even the first employee to log in can make a trade, providing instant liquidity and price discovery.

8.2 Currency and Incentives

-

Virtual Currency & Prizes: Due to regulatory constraints (CFTC) on real-money betting, most enterprises use a virtual currency system (e.g., "Points"). These points can be exchanged for tangible rewards (gift cards, gadgets) or intangible rewards (lunch with the CEO, public recognition).

-

Reputation & Leaderboards: A public leaderboard is a powerful motivator. Being ranked as the #1 forecaster in the company carries significant status currency, signaling high potential to leadership.14

8.3 Dealing with Manipulation Risks

A frequent concern is manipulation: "Won't employees sabotage a project to win a bet?"

-

The "Slush Fund" Defense: Theoretical and empirical research suggests manipulation is difficult to sustain. If a manipulator tries to drive the price down artificially (without changing the project's reality), they create an arbitrage opportunity. Honest traders will see the price is too low relative to reality and buy the cheap shares, pushing the price back up and taking the manipulator's money.35

-

Incentive Alignment: The career cost of being caught sabotaging a project far outweighs the value of a $50 gift card. Furthermore, compliance monitoring can flag suspicious trading patterns just as in financial markets.38

9. The ROI of Truth: Business Value Analysis

The Return on Investment (ROI) for a prediction market is calculated by comparing the Cost of the Market against the Value of Avoided Error.

9.1 The Formula for Prediction ROI

$$ROI = \frac{(\text{Value of Avoided Failure} + \text{Value of Optimized Allocation}) - \text{Market Cost}}{\text{Market Cost}}$$

Consider a pharmaceutical R&D portfolio 39:

-

Scenario: A drug candidate has a 10% actual chance of success, but the project team reports 60% due to optimism bias.

-

Cost of Error: Funding a doomed Phase III trial costs $50M+.

-

Market Intervention: A prediction market accurately prices the success probability at 15%.

-

Action: Management kills the project early ("Fail Fast").

-

Savings: $50M avoided loss.

-

Market Cost: $100k for software + $50k in incentives.

-

Result: The ROI is exponential.

Even in smaller contexts, such as IT project management, avoiding a 20% budget overrun on a $10M project saves $2M. The market pays for itself with a single correct signal.

10. Conclusion: The Market as a Strategic Asset

The implementation of an enterprise prediction market represents a shift from consensus-based management to evidence-based management. It acknowledges that the smartest person in the room is not the person at the head of the table, but the room itself.

By creating a platform where truth is profitable and ambiguity is expensive, the enterprise can:

-

Eliminate the "Green-shifting" of status reports.

-

Discover risks months before they appear on a dashboard.

-

Identify hidden talent (the quiet superforecasters in the rank and file).

-

Make capital allocation decisions based on probabilities, not politics.

While not a panacea, the prediction market is a "game changer" because it aligns self-interest with the collective good of truth-seeking. In an era of increasing volatility and data overload, the ability to synthesize signal from noise is the ultimate competitive advantage. The question is not whether the enterprise can afford to implement a prediction market, but whether it can afford to continue making decisions without one.

About Vinfotech

Vinfotech builds world-class prediction market solutions like Kalshi or Polymarket. Our proven core engine features battle-tested mechanics with AMM and order book support at a production-ready scale. Whether you need white label or full source code, we provide full customization to meet your specific compliance and operator needs. We also do enterprise prediction markets for internal forecasting. Contact Us today for a demo.

About Vinfotech

Vinfotech creates world’s best fantasy sports-based entertainment, marketing and rewards platforms for fantasy sports startups, sports leagues, casinos and media companies. We promise initial set of real engaged users to put turbo in your fantasy platform growth. Our award winning software vFantasy™ allows us to build stellar rewards platform faster and better. Our customers include Zee Digital, Picklive and Arabian Gulf League.